The strategic importance of soil, water and food in the early-mid 21st century

14 april 2017This article has been published here in the scope of the European Citizen Initiative (ECI) People 4 Soil

Key Points

- Freshwater scarcity is emerging as a critical systemic risk worldwide. While the global population has tripled over the past century, our use of water has increased sixfold.

- More than 95 per cent of humanity’s present food supply is produced from the soil.

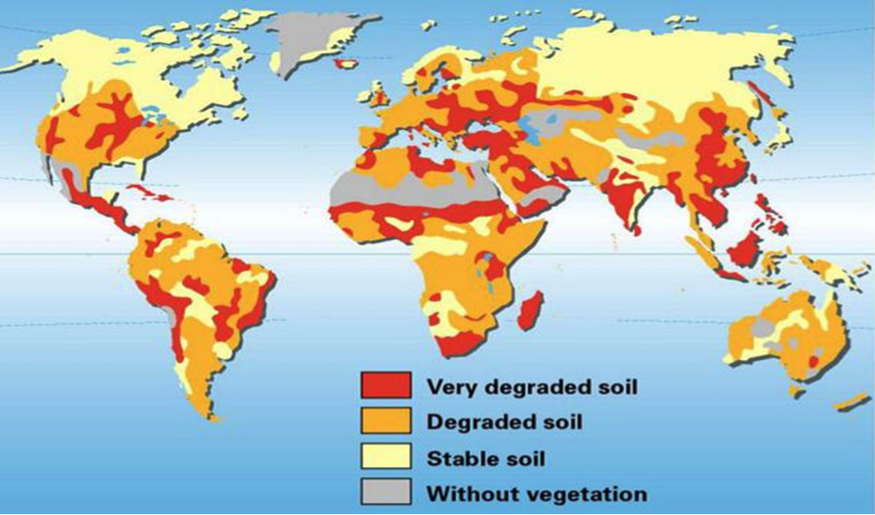

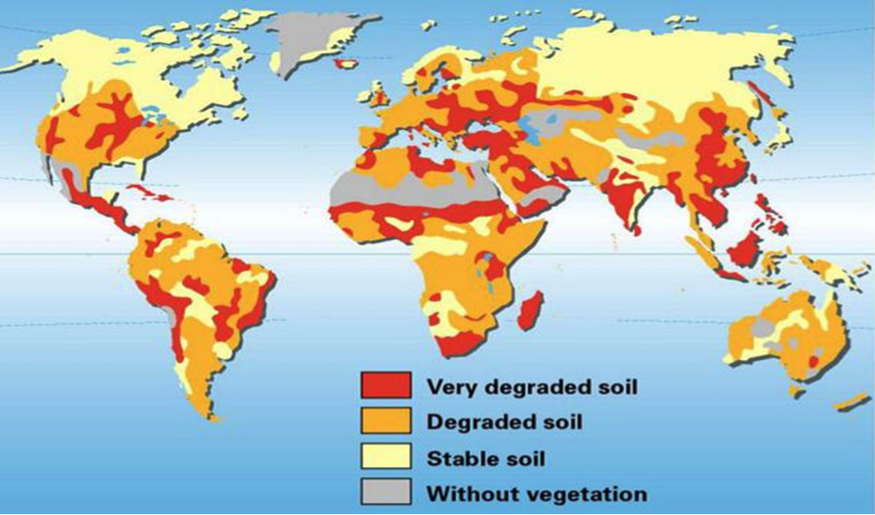

- Some 40 per cent of soil used for agriculture globally, is classed as degraded or seriously degraded – i.e. 70 per cent of the topsoil has been lost.

- The UN FAO has projected that for the planet, net land under crops may have to increase by some 70 million hectares by 2050 to meet predicted global food needs.

- The loss of food security – through climate (change?) or the loss of soil and water resources – is a major factor in people deciding to quit their homelands in search of new life, whether as economic migrants ahead of a crisis they have foreseen or as refugees fleeing a disaster.

Summary

Emerging scarcities of fresh water and topsoil, combined with the impact of climate change on regional food production, highlight the growing strategic significance of these primary resources for human survival, health and wellbeing as potential drivers of conflict and mass migration to 2050 and beyond. Conversely, there is mounting evidence that conflict and out-migration are far less likely in regions that are well-fed and where these primary resources are well-managed and not disputed-over. We argue with a global population approaching 10 billion in the 2060s, soil and water will be increasingly critical elements in global, regional and national security and must be factored into defence, security and sustainability planning at all levels. The role of food, land and water security in keeping the peace should be more widely understood and acted on.

Water

Freshwater scarcity is emerging as a critical systemic risk worldwide. Of all the emerging global resource scarcities (oil, strategic minerals, timber, fish etc) it is the one arriving most rapidly and universally.

To support the average citizen of Earth takes around 1,386 tonnes of fresh water a year. This ‘water footprint’ consists of all the water used to produce our food, consumer products, or provide the services on which we rely: our indirect use of water is many times larger than our personal use. In total, humanity uses more than 9 trillion tonnes of fresh water annually. While the global population has tripled over the past century, our use of water has grown sixfold.(1)

Two thirds of the human population – more than 4 billion people – already face acute water stress at least one month a year. About half of these live in India and China.(2)

The combination of growing populations, rising economic demand for food, megacity and industrial water consumption and climate change mean that “The ultimate consequence is that, by 2030, demand for water could be 40% greater than supply available,” according to a study by the UN University.(3)

Key elements of contemporary water scarcity are:

- The dire condition of the world’s major rivers, especially in semi-arid regions. The impact of their 6,000+ dams on downstream food and water security.(4)

- The drying up and pollution of lakes and inland seas worldwide.(5)

- Over-exploitation of groundwater (95% of Earth’s fresh water) in every region where it is used to grow food or support megacities and the energy sector. One third of the world’s major groundwater basins are now rated ‘in distress’.(6)

- Unprecedented decline in mountain glaciers (which supply major river systems).(7)

- Impact of climatic fluctuations on regional water supplies in eg California, Sao Paulo (Brazil)(8), central India(9) and China(10).

- Increasing frequency of drought in countries that seldom before experienced it, eg New Zealand(11), UK(12).

- Growing confrontation between farmers and energy corporates (coal, gas, oil, tar sands etc) over access to, and use of, water around the world(13).

The risks of conflict over water scarcity have been flagged by many eminent figures, notably UN chiefs Boutros Boutros-Ghali, and Ban Ki-Moon: “(water scarcities) create tensions in conflict-prone regions. Too often, where we need water we find guns.”

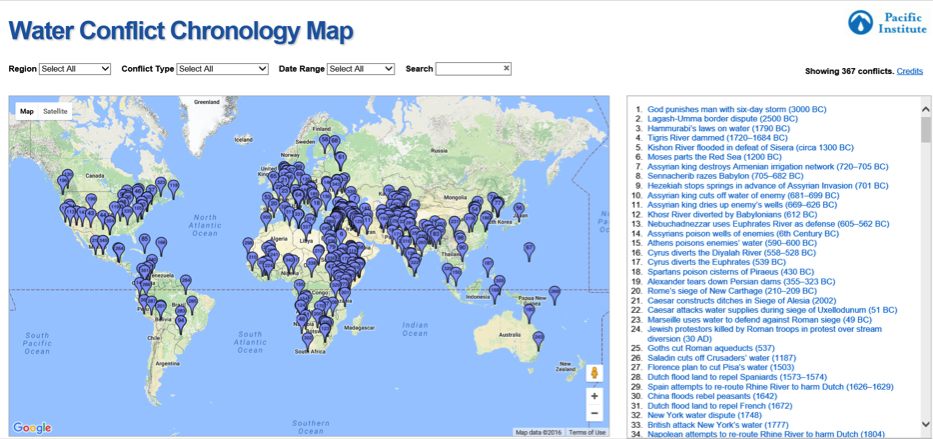

Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute maintains a timeline documenting water conflicts over the past 5000 years, noting a rise in both intensity and frequency in the 21st century: http://www2.worldwater.org/conflict/timeline/

Together these factors point to increasing scarcity of fresh water at a time of strongly rising demand, leading to potential for conflicts at various levels.

Regions where the risk of water scarcity leading to mass migration include:

- The North China plain where the aquifer that feeds 400m people is two thirds empty and is a major factor in Chinese land-grabs in Africa and elsewhere.

- The north Indian plain, the bread-basket of India which feeds 700m, where groundwater levels have been falling at 1 metre+ a year for over a decade.

- The Middle East, where acute water scarcity is a factor in the Syrian crisis, in international disputes (eg Israel/Syria) in Iraqi instability and Saudi/Emirates land-grabs in Africa.

- North Africa, where a food-basket failure on the scale of the one which brought down the Roman Empire in the 3rd century, could lead to massive migration into southern Europe.

- In the US central mid-west where it is estimated that water taken in the last 150 years will require 6000 years to replenish.

- Central Asia where drought and dam-building threaten the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers which supply several nations.(14)

Water crises ranked first in the World Economic Forum’s list of most impactful global risks for 2015, and third in 2016 (having been overtaken by climate inaction and weapons and mass destruction).(15)

The WEF’s ‘most likely’ risk was “largescale involuntary migration” triggered by conflict, extreme weather events (climate failure) and natural disasters.

Land

More than 95% of humanity’s present food supply is produced from the soil. However, that may not always be the case in future.

“A rough calculation of current rates of soil degradation suggests we have about 60 years of topsoil left,” Sydney University’s Professor John Crawford warned in a TIME magazine interview in 2012.

“Some 40% of soil used for agriculture around the world is classed as either degraded or seriously degraded – the latter means that 70% of the topsoil, the layer allowing plants to grow, is gone. Because of various farming methods that strip the soil of carbon and make it less robust as well as weaker in nutrients, soil is being lost at between 10 and 40 times the rate at which it can be naturally replenished,” he said.(16)

Soil degradation – Graphic: Philippe Rekacewicz, UNEP/GRID-Arendal

In contrast the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation has projected “that for the world as a whole, net-land under crops may have to increase by some 70 million ha by 2050” in order to meet predicted global food needs.

The US Geological Survey has estimated that human activity – mainly farming and land development – is causing the loss of about 74 gigatonnes of topsoil every year(17). This makes it one of the largest, if not the largest, human impact on the planet.

The University of Sheffield, in a 2015 paper, noted that nearly 33 per cent of the world’s arable land had been lost to erosion or pollution between 1975 and 2015.(18)

Authors such as Jared Diamond and David Montgomery have documented how soil loss contributed to the collapse of previous civilisations, including the Mayans, Greeks and Romans.

In the drylands, which account for 44% of the world’s food production system (including most of Australia), “arable land loss (is) estimated at 30 to 35 times the historical rate”, according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)(19). On average 12m additional hectares are being lost to desert each year. Paralleling this is a net loss in world forest cover of 6.6 million hectares/year.(20)

UNCCD executive secretary Monique Barbut links land degradation with the Syrian crisis and civil war, and conflicts in the Sahel, Mali and Darfur: “land is so closely linked to basic human needs, such as access to food and water. If land degradation interferes with the fulfilment of these needs, it can lead to conflicts over scarce land and water resources, spark food riots or turn smallholder farmers into refugees”.(21) Conversely, she notes, “The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and Sahel Initiative is bringing a coordinated and harmonised response to food security and peace.”

The United Nations Interagency Framework Team for Preventive Action has noted that land conflicts tend to become violent when they are “linked to wider processes of political exclusion, social discrimination, economic marginalization, and a perception that peaceful action is no longer a viable strategy for change”. The framework goes even further and states that “land issues readily lend themselves to conflict. Land is an important economic asset and source of livelihoods; it is also closely linked to community identity, history and culture. Communities, therefore, can readily mobilize around land issues, making land a central object of conflict.”

Traditionally famine has been viewed as a consequence, rather than a driver, of warfare. However, the Oslo Peace Research Institute challenged this perception in a paper arguing the risks of conflict were in recent decades much higher in regions suffering insecurity of food land and water – and much lower in places (such as Europe, North America or Australasia) where those resources were secure.(22)

These observations, and many more beside, support a view that food, land and water will play a more critical role in global security and the risks of conflict during the middle part of the 21st Century – and equally, that securing them can reduce the tensions that lead to war.

Finally, it should be noted that, while the world currently wastes up to 40% of its food in the production/market chain – enough to feed 3 billion people – no-one has yet devised an affordable system for redistributing food from surplus regions to deficit regions which cannot afford to pay for it on the scale required to overcome hunger. The proven solution lies in protecting and enhancing local food sufficiency through care of land, water and enhanced production systems. Furthermore, the waste can be eliminated by recycling nutrients through the megacities in advanced ‘urban agriculture’ systems.

Climate: threat multiplier

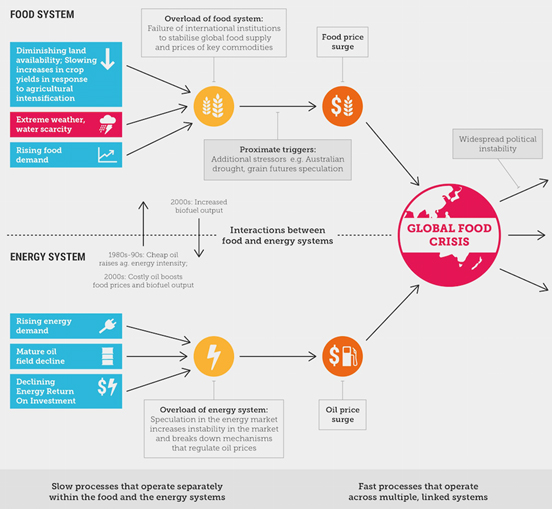

Climate will have a major influence over geopolitical security and risk of conflict in the C21st, primarily through its impacts on the food chain.

As former-US Secretary of State John Kerry observed in February 2014: “In a sense, climate change can now be considered another weapon of mass destruction, perhaps the world’s most fearsome weapon of mass destruction.” In 2015 a Pentagon study found climate change is a security risk, “because it degrades living conditions, human security and the ability of governments to meet the basic needs of their populations”. More recently, the UK’s Climate Envoy, Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti, said it posed as grave a threat to Britain’s security and economic resilience as terrorism and cyber-attacks.(24)

Climate change is, in effect, a threat multiplier of the risks already generated through insecurity of the primary resources of food, land and water.(25)

Mass migration

Food insecurity was a factor in the mass migration of 10 million Bangladeshis into India in the 1970s. Drought and failing agricultural systems are thought to have driven 1.5 million Syrians out of rural areas and into cities in the build-up to a civil conflict that led to 11 million Syrians fleeing their country. While scarcities of food, land and water seldom, of themselves, directly trigger conflicts – Darfur, Rwanda and Somalia may be exceptions – they are potent drivers in the background. As farmer and former US President Jimmy Carter said: “There can be no peace until people have enough to eat. Hungry people are not peaceful people.”(26)

Likewise, the loss of food security – through climate or loss of the necessary soil and water resources – is a major factor in people deciding to quit their homelands in search of a new life, whether as ‘economic migrants’ ahead of a crisis they have foreseen or as refugees fleeing a disaster. The exceptions to this were the Russian and Chinese famines of the mid-20th Century, when people chose to die where they were rather than move to foreign, largely-unknown countries and cultures. In the 21st century, with its ubiquitous mass culture of the internet and social media, people may be more inclined to seek food and security elsewhere.

This poses the undoubted risk of migration events numbering in the tens, possibly even hundreds of millions, depending on the scale of the resource failure – as Europe has recently experienced, on a more limited scale, from the Middle East and Africa.

It is important to understand that such disasters are preventable, with sufficient recognition of the driving factors and suitable preventative strategies.

In the C21st, we argue, the risk of mass migration events and conflicts driven by insecurity of food land and water is very much higher than in any previous age of human history. Food land and water must therefore be viewed as strategic elements of defence and international security as essential as naval fleets, air power or armies. Neglecting them will raise the risk of conflict and mass migration sharply – while preventing them will yield a peace dividend by removing an important casus belli.

It is time to recognise food, land and water as fundamental strategic elements in the world’s future defence and border protection policies. Great investment and knowledge sharing in all three will deliver a significant peace dividend globally.

Guest author

Julian Cribb, April 14, 2017

Julian Cribb is an Australian author and science writer. His recent books include “The Coming Famine” (UCP 2011), “Poisoned Planet” (A&U 2014) and “Surviving the 21st Century” (Springer 2017).

Resources

- Cribb JHJ, Surviving the 21st Century, Springer 2015; Dry Times, pp 39-43

- Mekonnen MM and Hoekstra AY, Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Science Advances, 12 Feb 2016. http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/2/2/e1500323

- Schuster-Wallace C.J. and Sandford, R. 2015. Water in the World We Want. United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, 2015. http://inweh.unu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Water-in-the-World-We-Want.pdf

- International Rivers. 2014. The State of the World’s Rivers. August 25, 2014. http://www.internationalrivers.org/worldsrivers/ and Howard BC. 2016. 8 Mighty Rivers Run Dry from Overuse, National Geographic, http://environment.nationalgeographic.com.au/environment/photos/rivers-run-dry/

- Many of world’s lakes are vanishing and some may be gone forever, New Scientist, 4 March 2016. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2079562-many-of-worlds-lakes-are-vanishing-and-some-may-be-gone-forever/?utm_source=&utm_medium=&utm_campaign= Peryman L. 2012. Unchecked industry reduces land of a thousand lakes to a struggling few, Probe International, 20 July 2012. http://journal.probeinternational.org/2012/07/20/unchecked-industry-reduces-land-of-a-thousand-lakes-to-a-struggling-few/ Lakenet, 2015 http://www.worldlakes.org/index.asp

13th World Lakes Conference, Wuhan, China, 2008. http://www.globalnature.org/30604/EVENTS/World-Lakes-Conference/02_vorlage.asp - NASA, Study: Third of Big Groundwater Basins in Distress, July 2015. http://www.nasa.gov/jpl/grace/study-third-of-big-groundwater-basins-in-distress

- World Glacier Monitoring Service. 2015. Global Glacier Changes: facts and figures. http://www.grid.unep.ch/glaciers/pdfs/5.pdf

Zemp M et al. 2015. Historically unprecedented global glacier decline in the early 21st century, Journal of Glaciology, 30 July 2015. - TIME, 2015 A Megacity without Water, http://time.com/4054262/drought-brazil-video/

- The Economist. 2015. Why India has a water crisis. http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2016/05/economist-explains-11

- Daniel Shemie and Kari Vigerstol, Why China has a water crisis. World Economic Forum, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/04/china-has-a-water-crisis-how-can-it-be-solved/

- http://www.climateoutcome.kiwi.nz/drought.html

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/08/15/absolute-drought-in-southern-england-as-rainfall-plummets-below/

- See https://www.google.com.au/#q=farmers+v+frackers

- http://thediplomat.com/2015/06/thirsty-yet-central-asias-coming-water-crisis

- http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GRR/WEF_GRR16.pdf

- Crawford J. 2012. What If the World’s Soil Runs Out? TIME. 12 December 2012. http://world.time.com/2012/12/14/what-if-the-worlds-soil-runs-out/

- Wilkinson BH and McElroy BJ. 2007.The impact of humans on continental erosion and sedimentation, Geological Society of America Bulletin, Geological Society of America Bulletin, January/February, 2007, v. 119, no. 1-2, p. 140-156.

- Cameron D, Osborne C, Horton P and Sinclair M. 2015. A sustainable model for intensive agriculture, University of Sheffield. 2 December 2015. http://grantham.sheffield.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/A4-sustainable-model-intensive-agriculture-spread.pdf

- http://www.unccd.int/en/programmes/Event-and-campaigns/WDCD/Documents/DLDD%20Facts.pdf

- UNFAO, 2015. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. How are the world’s forests changing? 7 September 2015 http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4793e.pdf

- http://newsbox.unccd.int/imgissue/UNCCDNews6_1.pdf

- De Soysa I and Gleditsch NP. 1998. To Cultivate Peace: Agriculture in a World of Conflict, PRIO, 1999.

- http://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/612710

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/jun/30/climate-change-security-threat-envoy

- Steffen W. Climate change: the ultimate threat multiplier. 2015. http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/climate-change-the-ultimate-threat-multiplier/

- Carter J, First step to peace is eradicating hunger. International Herald Tribune. June 17, 1999. http://www.nytimes.com/1999/06/17/opinion/first-step-toward-peace-is-eradicating-hunger.html